You don’t have to be a market analyst to see that many service businesses fail regularly and spectacularly when it comes to keeping customer commitments. Spares not in stock, technicians showing up with the wrong part, and missed appointments are issues we’ve all experienced from our service provider. As further evidence, the joke of the cable guy who promises to show up between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. has become a permanent fixture in our culture.

And the criticality that service operators fix this issue is readily apparent from industry research. According to Glance Technologies, a provider of CRM software, 91 percent of customers who had a bad customer experience won’t be willing to do business with your company again.[1] And Walker, a customer experience consultancy, predicts that service will overtake all other purchase factors by the year 2020.[2] So the service imperative is clear to anyone paying attention.

But the hard question remains: why do service businesses — especially those providing service at the customer premise — seem to fail much more often than what customers would expect as normal? Surprisingly, there are a number of factors unique to services that conspire to make consistently hitting high customer service a tough target.

And, to complicate the issue, many service businesses are evolving to become total solution providers, where optimizing their supply chain becomes even more critical. Point-of-entry customer requirements are becoming more complex across industries. As a result, many service businesses have underperformed in areas such as labor utilization, asset reliability, response time and service quality. In my experience, optimizing the service supply chain requires capabilities and technologies that are unique only to the service business; traditional product-focused solutions will not work.

Why service businesses struggle with good service

Service businesses truly are unique animals when compared to relatively stable and “flatter” models like wholesaling or product manufacturing. Not to say those are easy businesses to manage, but it’s very common that the complexity factor of a service business is a hundred- or thousand-fold more than traditional product businesses.

For example, an industrial OEM may have a total product line of 500 active SKUs, while its equipment repair business may be managing 250,000 active SKUs of repair parts. A large consumer products manufacturer may be delivering to twenty-five customer depots, while a product support business may have 20,000 customer sites it serves across a large geography.

The following table provides a snapshot of the complexities found in services, along with the operational implications that service managers have struggled with.

|

Unique characteristics |

Implication for operations |

|

A significant portion of demand is not driven by historical demand, but by special projects and the annual cap-ex budgeting process |

Planners must rely much more heavily on human-driven demand planning and collaboration than statistical forecasting |

|

Typical order promise and commit must occur on a semi–real-time basis, often on an emergency basis |

Inventory service levels must be high on slow-moving, critical items, and availability data must be timely and accurate |

|

Demand can be sporadic, low volume and random; it’s highly volatile with strong seasonality |

Traditional time-series statistical forecasting will be ineffective |

|

Order profiles are frequent, small volume, fragment orders (small units, many lines) with a large expedite percentage |

Fulfillment economies of scale in warehouse productivity and transportation will not be possible |

So, what’s the answer for service businesses?

Despite this bleak news, there is light at the end of the tunnel for service operators. The managerial talent that has spent the last 30 years transforming the product supply chain is turning its transformative eye on services. With its premium pricing, oversized margins and lower capital threshold, there is ample financial reason for operators to invest in new service capabilities.

Tried-and-true capabilities that have worked so well in the product supply chain for decades are finally being form-fitted to work equally well for service. This is evidenced by the explosion of decision support tools and enterprise systems that are focused on the service chain. Ten years ago the operations community had rarely heard of tools like Maximo, Servigistics, ClickSoftware and ServicePower, which all are now household names among aftermarket and maintenance managers.

PwC has identified the three leading capabilities that, when properly transformed from their product roots, can provide tremendous value in the services world.

1. Adapt a segmented supply chain structure

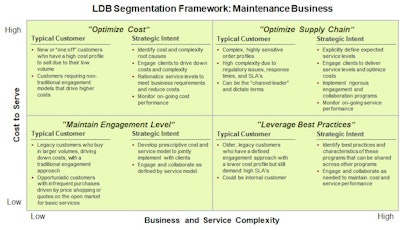

All supply chain managers understand that no business faces a monolithic set of demand signals or supply capabilities; there are always a variety of “embedded pipelines” that exist within a single supply chain. But this is never truer than in service. For example, a typical maintenance business faces a range of demand categories from stable, low criticality, easily planned replacement schedules, up to emergency, highly critical, unplanned “unit down” requests.

And on the supply side, the same maintenance business will face a variety of supply categories ranging from easily-sourced, low value, short lead time commodity consumables, up to highly-engineered, sole sourced, capitalized spares with lengthy lead times. The difference between these book-ends is obvious.

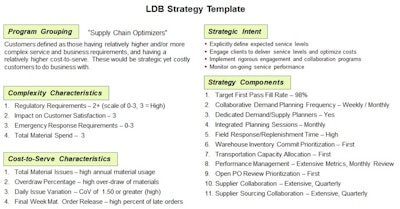

When combined, we call these different categories “logistically distinct businesses” (LDB) with each one having a unique set of demand, supply, service and cost attributes. As such, the primary LDBs in a service chain should each have its own tailored logistics response to ensure that scarce resources are optimally allocated to meet both cost and service targets. This strategic approach optimizes each “embedded pipeline,” or LBD, in a holistic fashion and eliminates the “squeaky wheel gets the grease” problem.

PwC calls this an engineered value chain approach and believes it to be the essence of being a service leader, because it enables surgical management of both costs and service levels. The following figures show how LDBs can be identified through customer segmentation, and how a customized logistics response can be developed for each.

2. Adapt a new form of integrated planning

In the product world, integrated planning has been known as sales and operations planning (S&OP) for decades. And as good as S&OP has been for manufacturers, it has been as equally bad for service operators. Volatile demand, highly variable part lead times, and an inability to “freeze” the production schedule as done in manufacturing has rendered product-based S&OP irrelevant for services.

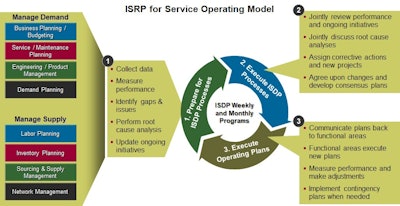

But there is a new, better model for services we call integrated service resource planning (ISRP). ISRP embraces the unique attributes of service and develops new mechanisms to address those challenges.

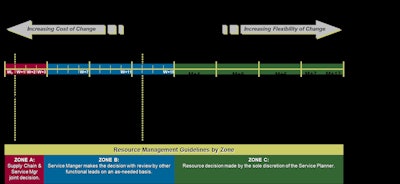

Similar to S&OP, ISRP uses a formal, procedure-driven approach to bring together the demand and supply functions of the service business. Its goal is to integrate demand requirements into supply, identify the gaps and implement contingency plans so the business can execute a feasible plan. Like S&OP, it will make use of concepts like time fences, demand forecasting and scenario analysis but will have transformed these to work for service operations.

The following figures demonstrate the structure and operation of ISRP for services.

|

Major Operating Characteristics of ISRP |

|

Demand forecasting is used but a more sophisticated, layered approach is employed along with a suite of analytics for forecast optimization

|

|

Planning time fences (PTF) are used but they are not used to “freeze” production, which is not feasible in service operations. Rather, the time fences are used to define the average lead time it takes to acquire or deploy a service resource

|

|

Service capacity is more surgically managed and aligned to the various demand streams

|

|

Scenario analysis should be in heavy use with advanced simulation to accommodate the large need in services to model a variety of scenarios, service levels and resources

|

3. Adapt new models of forecasting and inventory planning

A hallmark attribute of a service business is that a large percentage of the customer demand is randomized, often referred to as stochastic demand, which simply means that the random nature of the demand makes it impossible to forecast using traditional time series methods or heuristics. And even complex causal models will be insufficient to accommodate the complexities of this type of demand signal.

For one aircraft engine repair client, a PwC team found that 80% of its spares demand was statistically classified as stochastic, greatly complicating their demand planning. This has extremely negative implications for both accurate demand forecasting and service inventory planning.

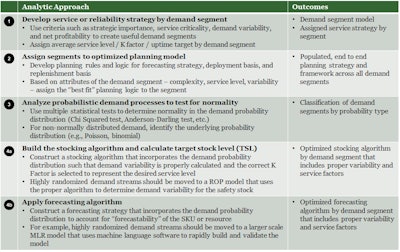

But there is a methodical, scientific approach to building an accurate forecast for services and service inventories. You’ll need the help of a data scientist and decision support tools that can support specific analytic approaches, but the benefits of accurate forecasting and inventory level-setting will enable significant value for the business.

The following table presents a high-level approach on how a service business can jointly attack its service forecasting and inventory challenges, and make them an effective part of their operations.

Robert A. Giacobbe, PwC Partner, Advisory Services

Robert A. Giacobbe, PwC Partner, Advisory ServicesAdopting these core three capabilities for services will enable the agility, precision and effectiveness that so many service operators struggle to achieve. Regardless, service operators will feel the pinch as investors demand improved financial performance and customers demand world-class service. The squeeze will come from both sides and will indeed drag service chains into the twenty-first century. Along the way, disrupters coming into mature markets will only bring added pressure for service operators to evolve to these new models or die.

But the good news is this: the blueprint exists for improved performance. However, it will require smart operators who can selectively tailor those existing capabilities to make them work for the unique attributes of services.

Robert A. Giacobbe is PwC Partner of Advisory Services. He can be contacted at [email protected] or 770-508-8955

©2018 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the US member firm or one of its subsidiaries or affiliates, and may sometimes refer to the PwC network. Each member firm is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. This content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors.

[1] https://www.ameyo.com/blog/customer-experience-statistics; article retrieved Aug. 9, 2018.

[2] https://www.superoffice.com/blog/customer-experience-statistics/ article retrieved Aug. 9, 2018; https://www.walkerinfo.com/knowledge-center/featured-research-reports/customers2020-1 article retrieved Aug. 9, 2018.